Wetland Enhancement Report

Reflections on the Wetland Enhancement project

This is the first of a 9-part post series by Tyra Enchill celebrating the Wetland Enhancement project and insights from the report, and her experiences on Phytology’s Ecology Internship last autumn.

Tyra is a multi/interdisciplinary ecologist in training and researcher from London. Her ongoing work is to question the political and socio-historical complexities of conservationism, human-environment relationships, and knowledge. In facilitating work towards social and racial justice, she is continually imagining what an integrated ecological justice practice could be, and how we might ally 'nature' in collective/embodied healing.

Introduction

In late September 2021, we began a year-long upgrade of our wetland to increase biodiversity and habitat diversity across the site, and improve access to our ponds for amphibians, birds, insects and mammals (including humans).

Those who’ve visited since may have noticed a new resident: a larger Ecology Pond opposite the medicinal garden, in place of the old modular ponds uprooted last autumn. Today we’re excited to share details of this transformation through the publication of our Wetland Enhancement report: a guide to our wetland’s history, why the ponds needed replacing, and our research, design and visions for this critical urban habitat in the long-term.

The report was written by our brilliant Urban Ecology team who supported the project through Phytology’s Ecology Internship from September – October 2021:

- Charlie Guy, Urban Ecologist

- Lauren Joyce-Smith, Nature Writer and Ecologist

- Mila G. Lawlor, Community Ecologist and Herbalist

- Salih Abdurrahman, Habitat Researcher and Ecologist

- Tyra Enchill, Interdisciplinary Ecologist

- Zoe Opiah, Urban Conservationist and Ecologist

You can download the full ‘Wetland Enhancement Report’ report here.

We extend our deepest gratitude to the remarkable people and communities who have shaped the new wetland: Our project managers, Michael Smythe, co-founder of the Bethnal Green Nature Reserve Trust, artist, and Creative Director of Nomad Projects; and Dimuthu Meehitiya, our resident Ecologist and Environmental Educator.

The Mayor of London, City Bridge Trust, London Community Response Fund, Groundwork, and the Bethnal Green Nature Reserve Trust for generously funding the Wetland Enhancement project.

And our neighbours, supporters and educators who enriched the wetland with their practical support, knowledge and generosity:

- Adelaide Bannerman, Curator in Residence at the Bethnal Green Nature Reserve

- Andrea Cox, Careers Consultant

- Ark Landscapes

- The Bethnal Green Nature Reserve Volunteers and Residents

- Charlie Guy, Urban Ecologist at the Bethnal Green Nature Reserve

- Daze Aghaji, Climate Activist; Artist in Residence at the Bethnal Green Nature Reserve

- Forest Fridays’ Ingrid Chen and Shilpi Choudhury, Outdoor Educators, and all the students

- GoodGym Volunteers

- Hayley Harrison, Artist in Residence at the Bethnal Green Nature Reserve

- Isabella Johnston, Forager at Rights for Weeds

- Jade and Sonny, Arborists and Tree Surgeons

- Jane Laurie, Local Bird Ecologist

- Joanna Pocock, Environmental Writer

- John Archer, Biodiversity Officer at London Borough of Tower Hamlets

- John Doe, Mini Digger Operator

- Karolina Leszczynska, Site Manager at Camley Street Natural Park at Camley Street Natural Park

- Lauren Joyce-Smith, Nature Writer and Ecologist at the Bethnal Green Nature Reserve

- Margaret Cox, Co-Founder of the Bethnal Green Nature Reserve Trust; Local Tenants & Resident Association Chair

- Mila G. Lawlor, Community Ecologist and Herbalist at the Bethnal Green Nature Reserve

- Neil Davidson, Landscape Architect; Chair of the Bethnal Green Nature Reserve Trust

- Nick Bridge, UK Foreign Secretary’s Special Representative for Climate Change

- Salih Abdurrahman, Habitat Researcher and Ecologist at the Bethnal Green Nature Reserve

- Shumaisa Khan, Medicinal Garden Coordinator at the Bethnal Green Nature Reserve

- Stephen Martin, Tower Hamlets Cemetery Park

- Sylvia Myers, Ecologist at the Natural History Museum

- Terry Lyle, Botanist and Environmental Educator

- Tom McCarter, Head of Gardens at the Natural History Museum

- Tyra Enchill, Interdisciplinary Ecologist at the Bethnal Green Nature Reserve

- Zoe Opiah, Urban Conservationist and Ecologist at the Bethnal Green Nature Reserve

Over the coming weeks, we’ll be sharing a series of posts celebrating contributions to the wetland refurbishment, insights from the report, and reflections on the Ecology Internship, written by Tyra Enchill.

Part 1 – Wetland History at the Bethnal Green Nature Reserve

The Bethnal Green Nature Reserve wetland was first created 30 years ago under the guidance of Terry Lyle, a cherished local botanist and environmental educator. It has since lived as an urban oasis for wildlife in the north-western neck of the site, opposite the Phytology medicinal garden. In 2002, a modular pond network was installed, made of four interconnected ponds lined with butyl, a synthetic rubber. This material gradually wears down and needs replacing within a few decades. The network’s first upgrade in 2016 saw the installation of six smaller ponds surrounding a larger pond to provide different habitat options for wildlife (e.g., a bog pond, deep pond, shallow pond).

I met the modular pond network on September 25th 2021, shortly before we began its excavation. It was my first day at the Bethnal Green Nature Reserve. I remember the wetland then as verdant, smelling of green and brown; its waters dark, still and soupy. Resting after a summer of service to its resident amphibians and visiting birds; quietly heaving with decades’ accumulation of organic matter and innumerable microscopic invertebrates. Well-contained, like each of the nature reserve’s ecosystems (its meadow, medicinal field, and woodland), all proud against the metal gates revealing the landscape beyond: cars; a playground; people who occasionally stopped, delighted, to ask what this place was, and what we were doing?

Before we began the Wetland Enhancement project, bright green carpets of least duckweed (Lemna minuta) crowded the ponds’ surfaces.

Duckweeds (Lemnoideae) are a subfamily of small, free-floating aquatic plants, widely known and begrudged for how quickly they spread across water. Some describe the effect this has on other life as hoarding light away from other aquatic plants; suppressing or ‘strangling’ competition. But I am wary of how language can project villainy onto certain species for how they survive and reproduce. The same goes for parasites, invasive species, microorganisms, and most insects – any life whose form may appear as dangerous, disgusting, unfamiliar or inconvenient, and then becomes entangled in our metaphors for good/bad. I have also seen bees and wasps perch on duckweed to drink water, and how well they keep ducks fed (hence their name!).

The challenge with duckweeds is that they can dominate in a pond, and biodiversity [1] declines where only a few species dominate. Although the old ponds looked and smelled verdant, they didn’t have many plant species or habitat opportunities for wildlife. Our aim is to nurture biodiversity by facilitating a habitat where a wide range of species can live – particularly as wetland species across the world are threatened with habitat loss and fragmentation, and because global biodiversity is declining at an unprecedented rate. At the local level, biodiversity is crucial for ecosystem health, function, stability, and resilience to change.

Another overabundant plant in the old wetland was yellow flag iris (Iris pseudacorus). They had long dropped their sunshine-yellow flowers but were recognisable by the masses of tall, sword-like leaves guarding each pond. They too can quickly spread, making it difficult for other plants to take root.

We heard that the wetland had, however, been historically successful in supporting smooth newts (Lissotriton vulgaris), a partially protected [2] amphibian. Newts eat invertebrates and live between damp nooks and crannies on land and bodies of water. Toads had greater difficulty establishing a population here, maybe due to the ‘island effect’. The nature reserve is surrounded by built-up land where amphibians can’t easily travel across. Being isolated from other populations, our toads likely had lower genetic diversity, and may therefore have been less resilient to new diseases and environmental stressors. But this is just one theory for why they couldn’t survive here; smooth newts also eat tadpoles. Or, there may not have been enough algae for the tadpoles to eat; or the water temperature may have been too cool under the shade of the trees.

On October 2nd 2021, we carried out an ecological survey using Imperial College London’s Open Air Laboratories (OPAL) Water Survey kit to better understand the historic wetland’s health and invertebrate community. In our pond samples, we found invertebrates such as water snails, leeches and flatworms, which tend to live in low-quality water. Though we found mayfly larvae, which can indicate medium-quality waters, bioindicators of a healthy pond were missing, such as cased caddisfly, dragonfly, damselfly and alderfly larvae.

The low level of invertebrate diversity, related to poor pond health, and low plant diversity, meant that we needed to encourage a healthier and more biodiverse wetland.

Footnotes

[1] Biological diversity, or biodiversity, is the variability of life on Earth or in a particular area. It can be measured at different scales from genes, to species and ecosystems. A wetland might be called biodiverse if there are many different species and types of organisms that live there, forming a complex community of plants, mammals, microorganisms, fungi and invertebrates.

[2] Smooth newts are protected by law in Great Britain under the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981. It is illegal to sell or trade them.

Part 2 – Ecological goals

Part 1 shared the wetland’s challenges with low plant and invertebrate diversity and poor pond health. These coincided with the end of the lifespan of the old modular pond infrastructure, which wears down over a few decades. Beyond installing a new pond liner, we used this window of opportunity to reimagine the site in context. How could we conserve and improve the wetland as a community resource for current and future generations (human and beyond)? How might a healthier wetland help to sustain the mosaic of ecosystems across the nature reserve? And what does facilitating biodiversity in and around the ponds look like, structurally?

The Wetland Enhancement project emerged as an ambitious plan to excavate the retired pond network and build a larger, healthier pond with an ecology-centred design. We began this work at the level of the habitat (the scale of what we could dig and plant). This meant revising the wetland’s architecture: the size, shape and depths of its ponds, as well as the vegetation and shelter available.

It feels intuitive to me to imagine how different microhabitats in and around a pond might support biodiversity. Sunny, warm areas encourage algae growth, feeding scavengers like pond snails and tadpoles, and filter feeders like water fleas. In a wetland’s damp peripheries, the rotting log yields to decomposers: fungi, woodlice, bacteria, mosses, beetles, some with preferences for certain types of wood or stages of decay. Stone edging and rock piles make crevices for invertebrates and amphibians to shelter, or platforms for reptiles to bask in the sun.

Strangely, it hadn’t occurred to me how foundational plant diversity is for nurturing biodiversity amongst invertebrates and other animals. Maybe this is a symptom of the ‘plant blindness’ I am slowly trying to remedy – the cognitive bias in forgetting plants as wildlife, or in grouping the many types of beings of this varied kingdom as one green mass. Plants become passive, overlooked as homogeneous; assumed to only background the variety of life our senses are more attuned to notice (like those that have eyes, or sing, or scuttle). It’s humbling to remember that plants are not only active agents in their environments and communities, producing oxygen, shaping terrain, gesturing to pollinators and herbivores/omnivores, making medicines, thorns and poisons, co-evolving; they are the primary producers on Earth on which most life depends. Plant diversity underlies (and is shaped by) micro- and macrohabitat diversity; it supports food diversity, functional diversity [3] and interaction diversity [4].

For instance, bog plants like the nectar-rich hemp-agrimony (Eupatorium cannabinum), medicinal meadowsweet (Filipendula ulmaria) and water figwort (Scrophularia auriculata) can grow in the damp places by ponds, servicing butterflies, bees, wasps, and even more specialised creatures like figwort weevils.

Shelves carved into the banks of a pond become anchors for plants with different preferences for water depth. Marginal aquatic plants like yellow flag iris and water plantain (Alisma plantago-aquatica) keep their feet wet in the shallows, roots submerged, bodies emerging tall above the water’s surface. These provide excellent shelter for invertebrates and amphibians (including their eggs). Floating plants like water lilies (Nymphaea spp.) absorb excess nutrients and create shade, preventing algae blooms and shielding aquatic animals from excess sunlight and predators. And then there are those that live their lives deep underwater: submerged plants which root in or grasp the mud, silt and detritus at the bottom of a pond, creating underwater ‘forests’ where invertebrates lay eggs, hunt, or escape from predators. Many of these plants, such as hornwort (Ceratophyllum demersum), are also important sources of dissolved oxygen in ponds.

When envisioning the new wetland’s ecology, we also thought about habitat connectivity [5]. The wetland will provide a reliable drinking reservoir for pollinators visiting the new wildflower and wetland meadows, and for small mammals living in the dead hedge a stone’s throw away. A greater diversity and abundance of invertebrates onsite may also improve food opportunities for birds and bats from the woodland, in turn attracting other wildlife including mammal predators (like cats and foxes).

In particular, we hope that the wetland will support more newts, especially the protected great crested newt (Triturus cristatus), toads, and dragonfly nymphs. Over time, we imagine certain bird species might arrive onsite to nest, drink or rest, such as reed warblers (Acrocephalus scirpaceus), sedge warblers (Acrocephalus schoenobaenus), water rails (Rallus aquaticus), black redstarts (Phoenicurus ochruros) and woodcocks (Scolopax rusticola). While our site is relatively small, it’s possible that a grey heron (Ardea cinerea) may see the pond and stopover.

Importantly though, this isn’t an exhaustive or prescriptive list. It’s more of a guide for whose arrivals we could celebrate as milestones as the ecosystem becomes more biodiverse. But we can’t say who will (or should) arrive, or when. I like to think of ecosystem management as experiments in hope, imagination and attention, with space for both facilitation and surrender. Without continued planning and care, the ponds would slowly become overtaken by organic sediment and vegetation, becoming marshier, then more meadow-like, and eventually a forested swamp. Yet even as we work to conserve this habitat, there is a need to practice de-centring our expectations and trusting in nature as the ecosystem continually experiments.

Footnotes

[3] Functional diversity: another dimension of biodiversity which represents the variety and abundance of functional traits, i.e., the range of roles performed by organisms, such as decomposition, nitrogen fixation or pollination. Functional diversity is measured at the level of the ecosystem and predicts ecosystem functioning. (Naeem, S., Duffy, J. E. and Zavaleta, E. (2012) ‘The functions of biological diversity in an age of extinction’, Science, 336(6087), pp. 1401–1406. doi: 10.1126/science.1215855.)

[4] Interaction diversity: variability amongst the characteristics of the network of linkages and relationships between species, e.g., competition, predation, parasitism, facilitation, and food webs. (ibid.)

[5] How organisms and materials move among patches of landscape. (Taylor P. D., Fahrig L., Henein K., Merriam G. (1993) ‘Connectivity is a vital element of landscape structure’, Oikos, 68(3), pp. 571–3.)

Part 3 – Social-ecological flourishing

Many of us live in societies that centre humans above all other species and bodies of nature. I think of urban, community-led green spaces not only as oases for wildlife, but socio-political and spiritual oases where we can practice more grounded relationships with ecosystems. There have always been worlds beyond extractive capitalism, financialised nature, human dominance. There still are: many worlds, resisting the tide. Here, at this nature reserve, nature is the priority. Still, I fell in love with the Bethnal Green Nature Reserve for their attention to both “environmental and social complexities” and their nurturing of both human and beyond-human nature, together. I often heard affirmations here that humans are parts of nature; we belong in ecologies.

To believe in and embody belonging means resisting against the disassociation from nature that I believe we must heal from, individually and collectively, especially in cities. We are not only interconnected with nature, but parts of nature. For conservationists, belonging also leaves behind the colonial and increasingly militarised “fences and fines” tradition of Western conservation [6] which has harmfully separated people from land for decades. We can cohabitate with what we want to preserve.

But I don’t think it’s a coincidence that those who are minoritised and disempowered by dominant socioeconomic and political systems are also those most alienated from environmental spaces and movements. Access to nature, to land, is about resources, power, and sovereignty. It’s also about food, economics, health, knowledge, and cultural and spiritual development. Around the world, Indigenous groups continue to see their historical land rights eroded through colonial projects (including conservation interventions) and state violence. Across diaspora communities globally, racialised peoples disproportionately suffer environmental injustices and estrangement from nature. In England, Black people and people of colour were estimated to make up only 1% of visitors to national parks in England, despite representing 10% of the general population [7]. In 2017, Natural England published data which showed that white people working in higher and intermediate managerial jobs were the most likely group to visit the natural environment (at 54.7%), while semi and unskilled manual workers from non-white ethnic groups were the least likely to (22.6%) [8]. As someone who navigates the world with marginalised backgrounds and identities (e.g., being working class; being a mixed-heritage Black and Asian woman, and neurodivergent…), I can attest to some of many intersecting barriers to accessing green spaces and conservation careers: time poverty, fatigue, underrepresentation, imposter syndrome, the demand for low or unpaid labour to gain experience, a lack of safe and inclusive spaces, as well as microaggressions and overt racism.

Yet I dream of a world where nature and environmental education are accessible to everyone, including (especially) city dwellers, young people and marginalised folks. I often envisage how, together, we might subvert interconnected environmental, ecological and social injustices through local pockets of resistance and knowledge. I wonder: what could biodiversity conservation and environmental movements look like if underrepresented and underserved communities were resourced to lead? How could our communities become more resilient and empowered through environmental education and access?

In addition to the ecological goals of the Wetland Enhancement project (see Part 2), it also sought to improve wetland access for people, increase engagement with wetland ecology, and provide an ongoing educational resource for schools, neighbours and visitors. We hope that the new wetland will become a multi-faceted, informal, multisensorial space to observe, experiment and learn as part of an intergenerational community over the next 30 years and beyond. (To quote Dr. Ayesha Khan: “when I say “community”, I don’t just mean other humans. I mean every living entity – plants, animals, microbes and all components of our ecosystems” [9].)

The Ecology Internship, which ran alongside the wetland refurbishment from September – October 2021, was part of this work. It provided an opportunity for six young people from underrepresented groups in conservation to gain experience in urban wetland development and ecosystem management. These were paid roles, which is fundamental for widening access and participation in the environmental field, yet unfortunately often isn’t the case, preventing many talented people from stepping into these critical roles. The internship also created learning and enrichment opportunities led by friends of the Bethnal Green Nature Reserve and environmental professionals across London. The rest of this series will share the experiences us interns (Charlie, Lauren, Mila, Salih, Zoe and me) shared, and the wonderful, locally-rooted network of ecologists, environmental educators and artists we were grateful to learn from/with.

Footnotes

[6] Also known as fortress conservation, this was a dominant model of conservation practice in the 20th century. It was based on the belief that biodiversity protection is best achieved by creating protected areas such as national parks, where ecosystems are isolated from human disturbance. The model was linked to settler colonialism in the United States before being exported to colonial Africa and other parts of the world. It has seen countless Indigenous groups forcibly excluded from ancestral lands with disastrous impacts on wellbeing, survival and justice, as well as ecosystems and conservation outcomes.

[7] Natural England. The Mosaic model – Engaging BME communities in National Parks. Data from annual visitor surveys, 2005-2007.

[8] Gov.uk. (2021). Visits to the natural environment. Available from: https://www.ethnicity-facts-figures.service.gov.uk/culture-and-community/culture-and-heritage/visits-to-the-natural-environment/latest [Accessed 3rd November 2022].

[9] Khan, A. (2022). Humans are not separate from nature, we’re part of it. Available from: https://wokescientist.substack.com/p/humans-are-not-separate-from-nature [Accessed 3rd November 2022].

Part 4 – Wetland excavation

Returning to September 25th 2021, the beginning of the 5-week pond refurbishment process and our first day as Ecology Interns. Our first task was to excavate the retired modular pond network. Autumn is a better time to carry out works as it’s a quieter time for newts, who no longer need pond access once the breeding season is over. Our aim was to cause the least disruption possible to the established ecosystem whilst embracing what felt like a paradox: conservation and habitat management can sometimes look like ecocide.

To excavate the main pond network, we used buckets to manually move its water into the three smaller, eastern ponds which would remain onsite (and are still here). We also translocated aquatic plants to these smaller ponds, and to temporary homes (large tubs of water) for replanting after the refurbishment. We punctured the old liner to drain any remaining water into the soil beneath, and shovelled 20 years’ debris and organic matter from the bottom of the ponds.

This took several days over a three-week period. After removing the pond liners, John and the volunteers helped dig a rough 9m (length) x 9m (width) x 1.8m (depth) pit which would house a new, bigger ecology pond. We were grateful to have had many helping hands from GoodGym, Bethnal Green Nature Reserve volunteers and a mini digger, which was kindly brought in by a gentleman called John Doe.

The excavation also involved removing large tracts of dominant plants across the wetland site, such as English ivy (Hedera helix) and alexanders (Smyrnium olusatrum). This intervention aimed to clear space and allow time for less successful competitors, such as violets (genus Viola) and damp-loving wildflowers, to gain ground and increase plant diversity. You’ll now find a biodiverse wetland meadow between the path and the eastern ponds where only ivy and few others used to live, planted now with edge and marginal pond plants such as water figwort, purple-loosestrife, hemp agrimony, Autumn crocus and many others [10]. ‘Weeds’, unplanted friends, have also happily emerged there this year. A favourite of mine is Ballota nigra, black (stinking) horehound, identified by its musty, acrid fragrance. I like how it declares itself with its smell, which, to humans, is “as offensive in odour as [the plant] is unattractive in appearance” [11].

Periodically clearing dominant plants will be an ongoing work. English ivy will slowly creep back. Again, this isn’t to vilify certain species. Ivy is an important Autumn nectar source for pollinators when it climbs and flowers. The challenge, when nurturing a space for biodiversity, is that it scrambles across and shades ground, preventing other plants from growing underneath.

To remove ivy, come close to the ground and take two handfuls, a little more than shoulder-width apart, parallel to the long rows of its roots. Roll away from yourself forcefully until the roots give way. It will smell fragrant; keep rolling and tugging and bundling the ivy in on itself to clear away mats at a time.

We also removed plum tree saplings which were emerging around the ponds, since their growing roots could damage the incoming pond liner. This was more difficult as they were hard and deeply rooted. Earlier, in Summer 2021, the large, mature plum tree had been cut down to make a light-filled clearing over the wetland. Its existence presented a dilemma: it was self-seeded, and over the years had come to overshadow the wetland area, naturally taking advantage of all the available moisture. The tree also held historical, emotional, and intrinsic significance to the nature reserve’s community. But its removal would allow sunlight to return to the wetland zone, supporting better pond health and creating the light variation necessary for habitat diversity and biodiversity.

It can feel grave to cut down a tree, and counterintuitive to uproot plants or excavate an established pond network. These decisions affect the entire ecological community and a community of people who care about the site. As difficult as it is to enact large-scale changes, we collectively anticipate that these decisions will lead to an overall increase in biodiversity, and a healthier wetland in the long term.

Footnotes

[10] See the Wetland Enhancement report, p.50, for a full planting list.

[11] Grieve, M. (2022). Horehound, Black. Available from: https://www.botanical.com/botanical/mgmh/h/horbla34.html [Accessed 11th November 2022].

Part 5 – Local knowledge

A challenge in naming the Wetland Enhancement project was conveying its multidimensionality. It’s quite a formal title for what was experientially a very playful and open experience, centred on a living, beloved part of the neighbourhood. The report is a relatively technical summary of the project (which has its place), but it feels balanced to also represent our time together as it was: joyful, collaborative and experimental. Those of us based at the Bethnal Green Nature Reserve had never built a pond before. What made the project possible was the diversity of experiences and ideas held by our extended community in London, which we could collectively consult, share and instigate, and everyone’s care toward the wetland, manifested as immense generosity and commitment.

To prepare for designing and building a new pond, we visited wetlands across London and talked with experts in wetland ecology, architecture and habitat management. We were also visited by artists, environmental workers and educators at the Bethnal Green Nature Reserve who shared locally specific ecological knowledge and approaches for engaging with the site.

This wider consultation was significant in our enrichment as ecology interns. It was inspiring to have exposure to so many varied roles within the environmental field, and to find ourselves embedded within an ecosystem of teachers, elders and peers in our city. This was also relevant to the ideas of empowerment and resilience through community-led conservation and environmental education that I touched on in Part 3 of this series. Through hands-on co-learning, everyone who shaped the wetland could each become contributors to / knowledge holders of the new pond’s architecture and ecology. This hopefully means that knowledge of the wetland can continue to be shared locally and intergenerationally, strengthening our base of caretakers in the long-term. The knowledge and skills we developed are also transferable to other places. We hope that by sharing our thinking and methods more widely (such as through these posts and the report) we can help to demystify the process of habitat creation and inspire similar urban wetland projects.

I want to revisit the consultations, conversations and workshops as they were a privilege to be a part of, and helpful for understanding the development of the new pond’s design. They’re also recommendations! I’d never been to any of the sites mentioned, but in each of them I found what I’ve been looking for in London: spaces to breathe, wander, observe, learn, restore. If you ever come across an exhibition, foraging walk or event by those mentioned, I would encourage you to join as they are some of the most inspiring people I’ve had the honour to meet.

Site visits

Lower Regent’s Canal, 11th October 2021

We had the opportunity to talk with Terry Lyle whilst browsing Lower Regent’s Canal in East London for planting ideas. Terry holds an extensive knowledge of botany and wetland ecology, and a close understanding of the Bethnal Green Nature Reserve’s wetland having overseen its original development 30 years ago.

We learnt that ponds need a balance of nutrients and light for plants to grow, and about the importance of oxygenating plants such as hornwort (Ceratophyllum dermersum) and water starwort (Callitriche stagnalis) for a healthy pond and clear water. Terry kindly brought samples of these plants from his pond at home, in bags of water, as well as water mint (Mentha aquatica), which can grow within water or on damp, muddy banks.

We noticed the canal’s ducks eating gypsywort (Lycopus europaeus) from an island of vegetation, and discussed how plants can provide both food and protective shelter for birds. We considered building a similar island in the new Ecology Pond to create a welcoming habitat for birds at a safe distance from predators, such as cats and foxes. Terry also highlighted invasive plant species to avoid, including common duckweed (Lemna minor) and floating pennywort (Hydrocotyle ranunculoides).

I had very limited field botany skills, and it was valuable to be introduced to so many interesting faces. From Shumaisa, the Phytology Medicinal Garden coordinator, and Mila, a fellow Ecology Intern and Community Herbalist, we heard about how people have traditionally interacted with some of the canal-side plants we met. Meadowsweet (Filipendula ulmaria) smells honey-sweet and was long used as a painkiller before willow bark, and then synthetic aspirin, became popular. We found saffron crocus (Crocus sativus), whose stigma and style [12] are used as a bright red, fragrant spice (the most expensive spice in the world by weight!). It was also warming to see fennel (Foeniculum vulgare) whose every part is edible, and to suck on its seeds as we walked. Shumaisa pointed out common rush (Juncus effusus), which was historically used to make candles by soaking the dried pith in lard and grease [13].

Tower Hamlets Cemetery Park, 11th October 2021

Tower Hamlets Cemetery Park is a nature reserve, heritage site and London’s most central urban woodland. It’s expansive and incredibly biodiverse. Dimuthu (resident Ecologist and Environmental Educator at the Bethnal Green Nature Reserve, Wetland Enhancement project co-lead, and Education Manager at Tower Hamlets Cemetery Park’s Soanes Centre) led a tour of four of its ponds. These each had distinct architectures and characteristics. One pond had very straight, vertical edges, resulting in hardly any life within its grey-brown water. Dimuthu highlighted the need to build the banks of a pond with gentle slopes to allow animals to easily enter and exit. Sloping banks also allow different plants to root at their preferred water depth. Another was a seasonal pond given its shallow depth and difficulty holding water in drier months. The visit highlighted how influential design features are in determining the health and properties of a pond.

Dimuthu had also collated a list of plants that we could translocate from Tower Hamlets Cemetery Park to help populate our new wetland. This included great reed ace (Typha latifolia), pendulous sedge (Carex pendula), common rush (Juncus effusus), marsh bird’s-foot-trefoil (Lotus pedunculatus), hornwort, Canadian waterweed (Elodea canadensis), water mint, British water lily (Nymphaea alba), lady’s smock (Cardamine pratensis), purple loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria), yellow loosestrife (Lysimachia vulgaris), water avens (Geum rivale), meadow crane’s-bill (Geranium pratense), marjoram (Origanum majorana), hemp-agrimony (Eupatorium cannabinum), common knapweed (Centaurea nigra) and common agrimony (Agrimonia eupatoria).

Wearing waders [14], we extracted these plants by hand. Sensorially, it was educational to be pond creatures for an afternoon. We are habitual onlookers of ponds (as terrestrial animals!), but it is also informational to be safely submerged, closely smell and look at their living waters, feel their temperatures and textures (cold, slimy, stringy), and activity.

When we returned to the Bethnal Green Nature Reserve, we washed the plants of as much residual duckweed as possible and kept them alive in tubs of water for the rest of the refurbishment. Since they can reproduce asexually by cloning themselves, we would have ideally washed away every last duckweed. But, given the amount of least duckweed we found in the pond this year, we hadn’t managed to (and I think that this would have been impossible to attempt with our resources). This is something I would note for other pond projects: it’s best to translocate plants from ponds that don’t have duckweeds or other ‘invasive’ plants living in them. This will help to save on the regular labour associated with managing these types of plants.

Camley Street Natural Park, 18th October 2021

A former coal yard 6 minutes’ walk from King’s Cross station which has been transformed into a 2-acre nature reserve with a wetland, meadow and woodland. Karolina Leszczynska shared her 11-year journey from working as a London Wildlife Trust volunteer to becoming site manager, and kindly gave us a tour.

The pond is fed by the neighbouring canal and surrounded by marshlands and reedbeds. It’s much bigger than our wetland, biodiverse and frequently graced with kingfishers, dragonflies, grey herons, cormorants, damselflies, butterflies, amphibians and warblers. Invasive species such as Japanese knotweed (Reynoutria japonica), red signal crayfish (Pacifastacus leniusculus) and terrapins (Malaclemys terrapin) present management challenges. As introduced species, they can easily disrupt ecosystems and outcompete historic plants and animal communities, reducing biodiversity. Floating islands in the neighbouring canal, made of pre-planted coir (coconut husk) mats, create valuable habitats for fish and invertebrates and help to purify the water. Karolina also showed us how deadwood is used to create habitat for invertebrates, such as endangered stag beetles.

The site feels welcoming and thoughtfully crafted with visitor engagement in mind: neat, natural fencing, viewing platforms, low pond-dipping platforms and a new Visitor and Learning Centre. Karolina shared valuable reflections on the importance of human access to green, biodiverse spaces and accessibility, whilst also reserving some areas for non-human nature. We also spoke about balance when managing a nature reserve. Wetland biodiversity takes extensive planning and physical labour to maintain, but in many cases, under-management is better than over-management. Observing, allowing, and only intervening when called to is what makes a nature reserve flourish with complexity over time.

The Natural History Museum, 18th October 2021

We visited the Wildlife Garden at the Natural History Museum in South Kensington, West London. The tour was led by Tom McCarter, Head of Gardens at the Natural History Museum; Sylvia Myers, Ecologist at the Natural History Museum; and Neil Davidson, Landscape Architect from J&L Gibbons Landscape Architects and Design and Chair of the Bethnal Green Nature Reserve Trust. It’s like a living gallery of British flora and fauna and more than 3,300 species have been identified in the garden since its opening in 1995.

It was valuable to hear recommendations for the depths we should build into our pond. The majority of pond-life live shallow depths of 10-15 cm, which means that shallow shelves are more important than deep waters. Most pond-dwelling animals are also very mobile and can move around and between ponds when water levels fluctuate seasonally (i.e., if areas overflow or dry out).

Neil is currently overseeing the redesign of the extensive parkland surrounding the Natural History Museum. He also designed the schematic for the new pond, pictured on page 28 of the Wetland Enhancement Report (downloadable below). It shows the pond as deepest at its centre, becoming shallower nearer the edges. We used this as a guide for designing a pond with gently sloping banks, allowing for different planting depths and access for amphibians and mammals.

Interestingly, we learnt that designing a pond for an urban setting isn’t too different from designing a pond in a rural environment like the British countryside. Our main concern in London is foxes, which have a habit of digging into and puncturing exposed pond liners. Since we have resident foxes at the nature reserve, this placed a time pressure on the stage between installing a pond liner and filling the pond with water.

Inside the museum, we were fortunate to tour the Angela Marmont Centre for UK Biodiversity [15]. The visitor space has a library, microscopes, and photo-stacking equipment to take high-quality photographs of natural history specimens. The staff were wonderful, and they encouraged visits as their facilities and services were underused. It’s a treasure for anyone looking to access resources, equipment or advice to identify an insect, bone, meteorite, fossil, etc. It’s also brilliant for illustrators who need visual references, or anyone who wants to gain skills in recording and monitoring biodiversity. We then explored the reference collections hidden away in the underbelly of the museum. There were hundreds, maybe thousands of specimens of plants, butterflies, beetles, and more…

Wick Woodland, 26th October 2021

Izzy Johnston of Rights For Weeds, a ‘celebration of nature’s overlooked edibles,’ took us on a foraging walk through Wick Woodland in Hackney Marshes, Northeast London. She blended the identification of food and medicine sources (e.g. hazel, elder, nettle) with folklore and foraging ethics. The wood was peaceful, and Izzy holds so much knowledge. This was on the last day of our Internship. It was valuable beyond words to experience London from a forager’s perspective; to access dietary alternatives and supplements outside of a shop, and to stay with certain plants that I’d ordinarily pass. Learning about historical relationships between human cultures and certain plants was an important reminder that the field of ecology is recent, and yet can co-exist with other ways of understanding nature and ecosystems which are older and beyond science.

As a last thought, one of the brilliant things about London is that there are so many resources and spaces to learn about nature and biodiversity, and all the above places are free to visit. I once believed that I’d have to leave the city to access ‘nature’ and to be involved in environmental work. I hope others who feel the same might be assured that it’s possible to find these here, too.

Footnotes

[12] Stigma: the sticky bulb in the centre of a flower. Style: the long, slender stalk in the centre of a flower, which holds up the stigma.

[13] The Rushlight Club. (1935). The Rushlight or Rush Candle of Old England. The Rushlight Journal, vol. 1., no. 4. https://www.rushlight.org/articles/juncus.html.

[14] High, waterproof trousers and boots or overalls which extend from the foot to the thigh, chest or neck.

[15] Natural History Museum. (2022). The Angela Marmont Centre for UK Biodiversity. https://www.nhm.ac.uk/take-part/centre-for-uk-biodiversity.html

Part 6 – Local knowledge (continued)

Talks at the Bethnal Green Nature Reserve

Alongside external visits, our learning was also informed by workshops and conversations held at the Bethnal Green Nature Reserve. I valued these opportunities to reflect on the impact of the Wetland Enhancement project on the nature reserve as a container for arts, ecology and education, and on our positionalities as entrants into environmental work (which we now understand takes many forms), starting within this ecosystem. These are shared below, supplemented a little from the report.

Hayley Harrison – Residency and Exhibition

Some of the wonderful people who nourished our thinking included Hayley Harrison, a multidisciplinary artist in residence at Phytology in 2021. Hayley works “with people, forgotten spaces and abandoned materials (human and non-human) to start conversations about our relationships with each other, places we call home and the non-human world” [16]. In response to her installation displayed throughout the site last year, I thought about how we often project human emotions, assumptions, desires, voices, and ways of creating meaning onto other beings. But how do other living beings experience the world? How do human-made entities find place and relationship in ecological communities?

To this last question, I think of the kebab boxes that can sometimes be found at the site’s margins, discarded by people, enjoyed by foxes, discarded again. If left, they could potentially take up residence for decades or centuries. I also think of the wartime bomb ruins and rubble throughout the woodland that now form part of the site’s terrain and soil composition. The existence of artificial or waste materials in designated sites for nature can raise tensions between romantic ideals of pristine wilderness and the realities of urban habitat management. I hope that there can be space to appreciate the complexity and hybridity of these worlds, which are not altogether human nor non-human. It is also possible to approach contaminants (both actual and metaphorical) curiously, to sensitively consider their histories, and the web of impacts that different objects and materials bring to the site.

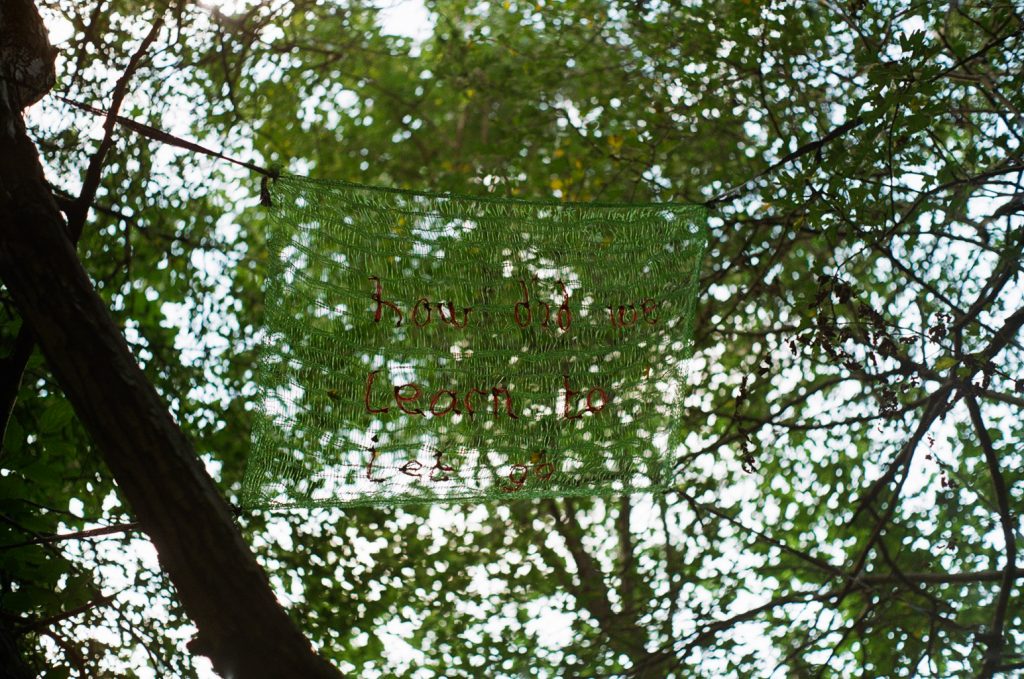

Hayley’s installation also brought up ideas around agency: how non-humans participate in human communities and art, whether actively through processes like decomposition that transform material culture, or passively via unbalanced relational practices, like coercion, or objectification. My favourite piece was a green kindling bag that read (in red embroidery): “how did we learn to let go”. I liked that it nearly disappeared in the tree canopy.

A Conversation with Nick Bridge, 11th October 2021

We were grateful to talk with Nick Bridge, the UK Foreign Secretary’s Special Representative for Climate Change in the weeks before the United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP26) summit. We held this conversation on the excavated site where the old pond network used to be, and where the new pond was ready to be built. It felt symbolic of a transitional period, onsite and globally.

The conversation highlighted the importance of transparency and accountability amidst the climate and biodiversity crises, particularly in government. It raised questions around the effectiveness of sustainable development goals set at a national level. Climate change will affect us all, but not equally. Those who are most politically and economically disempowered, people in the Global South, and those living in cities will be among the most impacted. Urban microclimates are already warmer than rural areas, which means that strategies for conserving biodiversity must consider the additional vulnerability of city flora and fauna.

While waiting for top-down changes in policy and legislation, which take time, we can begin preparing and developing adaptive responses now. Local initiatives such as ours are crucial for building community-specific social and ecological resilience. Building a wetland will help to mitigate the effects of storms, floods and warming, and hopefully provide refuge for wildlife over the next 30 critical years of climate change. I imagine that the Bethnal Green Nature Reserve will also be a place in the community where people might go to seek solidarity, refuge and solutions as we navigate a changing climate. During the heatwaves this summer, it was noticeable how much cooler the microclimate near the pond and beneath the trees was, compared to just outside the nature reserve. Once people can feel the tangible difference that wetlands make in an environment, I hope that small, informal, urban ponds might become more and more common.

Medicinal Garden Tour, 16th October 2021

Shumaisa Khan, coordinator of the Phytology Medicinal Garden, taught us about the plant medicines situated opposite the wetland, their many names, and histories of usage to support health. Shumaisa later researched medicinal wetland and damp-loving plants that could be introduced between the Medicinal Garden and wetland:

“I was mostly thinking of plants for the [pond] edge, so things like marshmallow, meadowsweet, maybe calamus. I also like horsetail, but it needs to be contained and kept an eye on as it spreads by spores. I also found this site [17] about medicinal aquatic plants, but again things like growth pattern, aggressiveness and size need to be considered for our context.”

Since then, Shumaisa has coordinated extensive changes in the layout of the Medicinal Garden to make it more accessible, and to create space for medicinal wetland plants right up to the pond’s edge. Meadowsweet [18] and marshmallow (Althaea officinalis) [19] have now been planted on the damp northern side of the pond, which is similar to the habitats that these plants naturally thrive in. I watered the young plug plants during a hot week in April. Though there is a need to save water (a valuable resource), having these thirsty plants in the wetland does reduce the need for irrigation.

Their placement also expands the wetland’s use by making it a site where people can access medicines. It has been particularly interesting to see people interacting with the tall stands of marshmallow over the summer. Their leaves are comfortingly soft and many people, myself included, are delighted to learn that the marshmallow is a plant. I have good memories of trying its pink and white flowers (which taste like the sweets, but more delicate), and its leaves (which are mucilaginous – slimy – like okra). Shumaisa or Mila, a fellow Intern and community herbalist, could share more about its medicinal properties. Briefly, its root can be used to soothe mucous membranes, coughs, stomach ulcers. But I also like that medicine can be so many things. I’m sure that some mechanisms of healing are triggered when a plant makes you laugh from joy and surprise, or when its texture feels like an embrace (inducing oxytocin?) I would like to test this next summer; they are a convenient height to hug.

The Birds of Bethnal Green, 9th October 2021

Local bird specialist Jane Laurie held a presentation about the birds which have lived in and visited the Bethnal Green Nature Reserve. These include species on the UK Birds of Conservation Concern Red List, which are considered the most threatened by the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds, such as starlings (Sturnus vulgaris), house sparrows (Passer domesticus), song thrushes (Turdus philomelos) and grey wagtails (Motacilla cinerea). Jane also suggested species we might be able to attract with new wetland features: reed warblers (Acrocephalus scirpaceus), sedge warblers (Acrocephalus schoenobaenus), water rails (Rallus aquaticus), grey herons, woodcocks (Scolopax rusticola) and jacksnipes (Lymnocryptes minimus). We learnt about identifying species through song, appearance and movement, and their ecological niches, including habitat and dietary needs. To attract a greater diversity of birds to the Bethnal Green Nature Reserve, Jane recommended:

- Reeds planted around the pond edge. These create habitat for invertebrates, which birds can feed on. Birds can also hide from predators in dense vegetation. Water rails, for example, are shy and elusive birds, preferring to keep to tall marsh plants and vegetation, and warblers need dense beds of common reeds (genus: Phragmites).

- Silver birch trees, which attract caterpillars (eaten by birds such as the blue tit). Reed warblers also love silver birch, and the bark makes great kindling for fires.

- Monitoring the fox population and their behaviour. Foxes prey on birds and can deter them from visiting the site. We can try to reduce their impact by creating places for birds where foxes can’t reach, such as the pond island, nearby trees and roost boxes. Edward Simpson (a neighbour, carpenter and site caretaker) has built and placed roost boxes around the site this year.

- Facilitating insect diversity. The greater the diversity of invertebrates, the greater the range of bird species (and other types of predators) we can support. We can attract and accommodate more invertebrates, such as worms, snails, aphids, beetles and flies, by introducing more flowering plants, adding to our dead hedge, and building log and rubble piles around the wetland.

- Abundant food options, particularly in early spring. Climate change is leading to caterpillars emerging earlier in spring, which can cause chicks hatching later in the season to go hungry [20]. Diverse food sources help young birds that have missed the short peak in caterpillar abundance. Supplying bird feeders and mealworms is controversial though, as they can cause unintended and unpredictable consequences, such as behavioural changes and disease transmission. We have therefore maximised alternative food options such as plant buds, nectar and seeds in the new wetland meadow, and are supporting invertebrates in and around the pond.

- Trees that purify air by capturing particulate matter, such as yew, conifers, silver birch and elder. Air pollution is a big problem in cities like London, and when air pollution is high, insects become scarce, which impacts bird populations.

- Patience. It takes time for new individuals to visit – especially larger-bodied birds like the grey heron. It takes even longer for populations to establish. Time allows us to observe what works and doesn’t work for bird diversity, and to make adjustments based on our observations. We can learn from the common pipistrelle (Pipistrellus pipistrellus) bats that have lived in the site’s woodland for years. Historically, they wouldn’t feed over the ponds due to trees obstructing their flight path and low insect populations. But they have begun to feed over the new pond at night. This is a huge win during the new wetland’s first year, as it could lead to more bats living onsite. We hope that birds will follow suit.

A key learning from Jane’s talk was the importance of facilitating biodiversity via food webs, and by providing habitat in response to the changing climate and species’ ecological needs. By building more dead hedges, log piles and dense planting with biodiverse vegetation, we will encourage greater insect diversity, which will support more bird and amphibian species, and consequently attract more mammal predators. Through increased biodiversity, we hope to see a more complex, dynamic, stable and resilient ecosystem. For example, the pair of ducks that visited the pond regularly over summer had an appetite for slugs, which gave the plants in the medicine garden some relief.

A Conversation with Adelaide Bannerman and Daze Aghaji, 26th October 2021

We talked with Adelaide Bannerman, curator in residence, and Daze Aghaji, climate activist and artist in residence, about their approaches to their practices, independently and in collaboration with one another. Their series of hand-painted texts, entitled ‘wecomewithourquestions’, was part of an intergenerational conversation between Adelaide and Daze, displayed on the large billboard in the southwest corner of the nature reserve in 2020 and 2021. The statement on the billboard at the time, ‘we speak in tongues about the thing(s) we love,’ hung in my mind. In my time as an Intern, it became clear how many communities use the nature reserve, and that there are as many ways of engaging and expressing love for the site as there are volunteers, residents and visitors.

Adelaide and Daze also spoke of how they inspired and mentored one another whilst working together. Daze shared her background and recent journey in becoming a climate justice activist and campaigner during university, eventually becoming the youngest candidate to stand in the EU parliamentary elections at 19 years old. A recurring theme was the importance of finding and using our voices to advocate for our communities and what we want to protect, and to feel empowered, whatever our age, to pursue what we believe in.

Nature Writing Workshop, 23rd October 2021

Joanna Pocock, an environmental writer, held a nature writing workshop to encourage us to tune in to our surroundings and frame our reflections through writing. Storytelling and poetry are extremely durable ways of storing and sharing environmental knowledge intergenerationally. Writing can also be a powerful tool to advocate for nature conservation. On an (inter)personal level, writing can become a medium for connecting our outer and inner worlds, and inviting others into what we notice.

We read a variety of poems and studies of nature before wandering the nature reserve. Each of us wrote a poem about our observations and experiences. Joanna encouraged us to listen to the space in its urban context: birdsong punctuated by trains from the Cambridge Heath overground station, people talking nearby, etc.

Nature Writing Workshop, 23rd October 2021

Joanna Pocock, an environmental writer, held a nature writing workshop to encourage us to tune in to our surroundings and frame our reflections through writing. Storytelling and poetry are extremely durable ways of storing and sharing environmental knowledge intergenerationally. Writing can also be a powerful tool to advocate for nature conservation. On an (inter)personal level, writing can become a medium for connecting our outer and inner worlds, and inviting others into what we notice.

We read a variety of poems and studies of nature before wandering the nature reserve. Each of us wrote a poem about our observations and experiences. Joanna encouraged us to listen to the space in its urban context: birdsong punctuated by trains from the Cambridge Heath overground station, people talking nearby, etc.

I was most struck by how ‘what we pay attention to grows’. Anything can become embossed against the ordinary field of perception, and start to speak, when another gives audience. I study biology and ecology for the infinite stories, lessons and metaphors that emerge from each body and phenomenon of nature. Everything alive is intricately inventive in strategies to survive, resist, adapt and express immeasurable histories of being, through form and behaviour. The waxiness of a leaf is a lesson learned over evolutionary time; it says to insects: ‘do not climb on me.’ The size of a territorial robin’s red breast can read: ‘I’ve been here longer than you.’

After writing, we read our poems together. Salih Abdurrahman has offered his poem for sharing:

Spirits in the trees,

In their own Solitude,

A silence unbridled,

Can we still be friends?

An old memory walks by,

Cascading a redundant wind,

In a sacred grove uncharted,

Rustling leaves by the robins as they play,

When the branches pass away,

A life secret we have lost

Irredeemable as the abyss echoes

Fading in time

To it we return evermore…

We also reflected on some of our complex relationships to creative writing and storytelling. Imposter syndrome seems to be a major barrier to writing and creating generally, and in my experience it can be hard to know one’s own voice. This makes supportive spaces to write and read communally so important. Like every species and being on Earth, there is so much perspective and story in each of us.

This workshop inspired a joint mindful ecological observation and writing workshop that Joanna and I held together in Autumn 2022, centred on the pond. (More on this later.)

Careers Workshop, 23rd October 2021

Andrea Cox, a careers advisor from King’s College London, held a workshop to explore the range of career prospects available within the environmental sector. We explored tools for better understanding our values, needs and dreams, such as the multidimensional Japanese concept of ikigai [21], and discussed ways to access ‘answers, advice, assistance, advocacy and alliance’ to aid our career development. As people who are underrepresented in the environmental sector, it felt important to recognise the barriers we were actively overcoming. It was also significant to have/hold a focused space to express our hopes and visions amongst peers and an experienced, knowledgeable supporter. A helpful exercise is to sit with another person, and each take turns to reflect on and actively listen to each other’s aspirations. Many dreams can sit underground until they are spoken, and having them heard can be the first step to realising them.

Throughout the Internship, I was grateful to work with Charlie, Lauren, Mila, Salih and Zoe. Everyone had parallel, yet distinct, interests and ways of connecting to the environment. It was inspiring to learn with and from eachother. I’m excited to hopefully see what we each end up doing as our journeys continue to unfold, and feel that the enrichment we received throughout the Internship will nurture our voices, aspirations and confidence for many years to come.

Footnotes

[16] Hayley Harrison. (2022). About – Hayley Harrison. https://www.hayleyharrison.co.uk/about

[17] Lilies Water Gardens. (2013). Edible and Medicinal Pond Plants. https://blog.lilieswatergardens.co.uk/2013/03/08/edible-and-medicinal-pond-plants/

[18] Meadowsweet (Filipendula ulmaria), a sweet-smelling flowering herb, has been used as a painkiller similar to aspirin for centuries. It has a wide variety of other traditional usages, from breaking fevers to treating upset stomachs.

[19] Marshmallow (Althaea officinalis) is a flowering plant which was originally used to make marshmallow sweets. The leaves and roots have medicinal uses for many digestive, respiratory, and skin conditions.

[20] Burgess, M.D., Smith, K.W., Evans, K.L. et al. (2018). Tritrophic phenological match–mismatch in space and time. Nature Ecology & Evolution, vol 2, pp. 970–975. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-018-0543-1

[21] Ikigai (生き甲斐), ‘a reason for being’, is a Japanese concept referring to a thing or practice that gives a person a deep sense of purpose and reason for living. It can be visualised as a combination of what you love, what the world needs, what you can be paid for, and what you are good at.